If you want to learn the facts and practical tips about running cadence, then you’ll love this up-to-date article.

I’ve read over 37 scientific papers and share these insights with you. Prepare yourself for some myth busting.

Continue reading or jump straight to the ideal running cadence calculator.

Content menu:

- What is running cadence

- How to calculate your current running cadence

- Does running cadence matter

- What is the ideal running cadence

- Running cadence calculator

- Do this to increase your running cadence

- Can my running cadence also be too high?

- Injured? Increase your cadence!

- Factors that influence the ideal stride frequency

- Here’s the cadence of professionals

- Measuring cadence with sport technology

What is running cadence

Running cadence is defined as the number of steps you take per minute (SPM) while running. Together with your step length, cadence determines your running speed.

There are several synonyms for running cadence. Some examples are:

- Stride frequency;

- Step rate;

- Strides per minute or Steps per minute

When looking at cadence numbers, it’s important to understand whether we are talking about steps or strides. It’s also important to know the metric unit: per minute or hertz (Hz).

Example: 160 steps per minute = 80 strides per minute = 1,3 Hz stride frequency.

In some rare situations, people talk about revolutions per minute (RPM). Probably because this is a common metric in cycling. Be aware that a “revolution” in running is a combination of 1 left and 1 right step. Therefore, 180 steps per minute (SPM) equals 90 revolutions per minute (RPM).

How to calculate your current running cadence

If you want to know what your current running cadence is, you only need a stopwatch or (smartphone) timer. Here’s an easy and practical way to measure your cadence:

- Count how often your left foot hits the ground in a 60 second time interval.

- Multiply that number by 2, to get the total amount of steps for both your left and right foot.

- That’s it, you’ve now measured your cadence in steps per minute.

Formula running cadence:

Cadence (SPM) = Total amount of steps (left and right) ÷ Time (minutes)

You can also simply use a smartphone app, sports watch or other sport technology to measure your cadence.

Does running cadence matter

Before you continue reading, you probably first want to know whether running cadence is important at all.

The simple answer is: yes, it is important!

Simply because cadence is one of the 2 factors that determine your speed. Remember: speed equals cadence multiplied by step length.

Formula running speed:

Running speed = Steps per minute * Step length

However, that doesn’t per se mean you need to focus on, or adjust your cadence. This depends on your current cadence – which you just measured – and your goal.

It’s good to start with comparing your current steps per minute with the “ideal” steps per minute.

What is the ideal running cadence

Let’s first define the ideal running cadence.

The ideal running cadence is the cadence that requires the least energy to run at a given speed. You could also call it the most energy efficient cadence.

If you are injured or trying to prevent injury, you may define the ideal cadence a bit differently. But let’s talk about that topic later on.

First some myth busting: 180 spm is not (always) the best cadence.

180 spm is not (always) the best cadence.

The idea that 180 spm is the best cadence comes from an observation at the 1984 Olympics. Jack Daniels counted the stride frequency of all his elite distance runners and found that only one out of 46 had a cadence below 180 spm. A myth was born.

The truth is that a good running cadence is highly individual. It can easily range somewhere between 150 and +200 steps per minute.

It depends on a lot of factors, like running speed (duh) and body height.

If you don’t have access to a lab, the best thing to do right now is to compare your cadence with the cadence of a large group of uninjured long-distance runners. Here you go:

Running cadence calculator

This running cadence calculator is the result of a scientific publication. It calculates the “ideal” running cadence, based on running speed and leg length (body height).

Calculate your ideal running cadence:

The calculator is based on a scientific formula that best describes the cadence of a large group of uninjured long-distance runners. In other words, it’s a comparison calculator based on running speed and leg length.

As a result, it’s not per se your ideal running cadence, but it’s a good way to start if you don’t have access to a lab.

Use the calculator and you’ll immediately get both your “ideal” running cadence and a link to the full scientific paper.

There are several reasons why your cadence should be higher or lower than the calculated cadence. We’ll talk about that in a bit. Let’s first learn how to increase your cadence or figure out if your cadence can also be too high.

Do this to increase your running cadence

There are multiple reasons why you would want to increase your running cadence. Here’s a short list:

- You compared your cadence with the “ideal” running cadence, using the calculator, and found out that your running cadence is too low.

- You consider yourself a beginner and learned that most beginners have a cadence that is too low.

- You have an injury and your physiotherapist tells you to increase your cadence.

- Your coach tells you that you should increase your cadence to run faster and more efficiently.

If so, here’s how to increase your cadence without increasing pace.

General recommendations

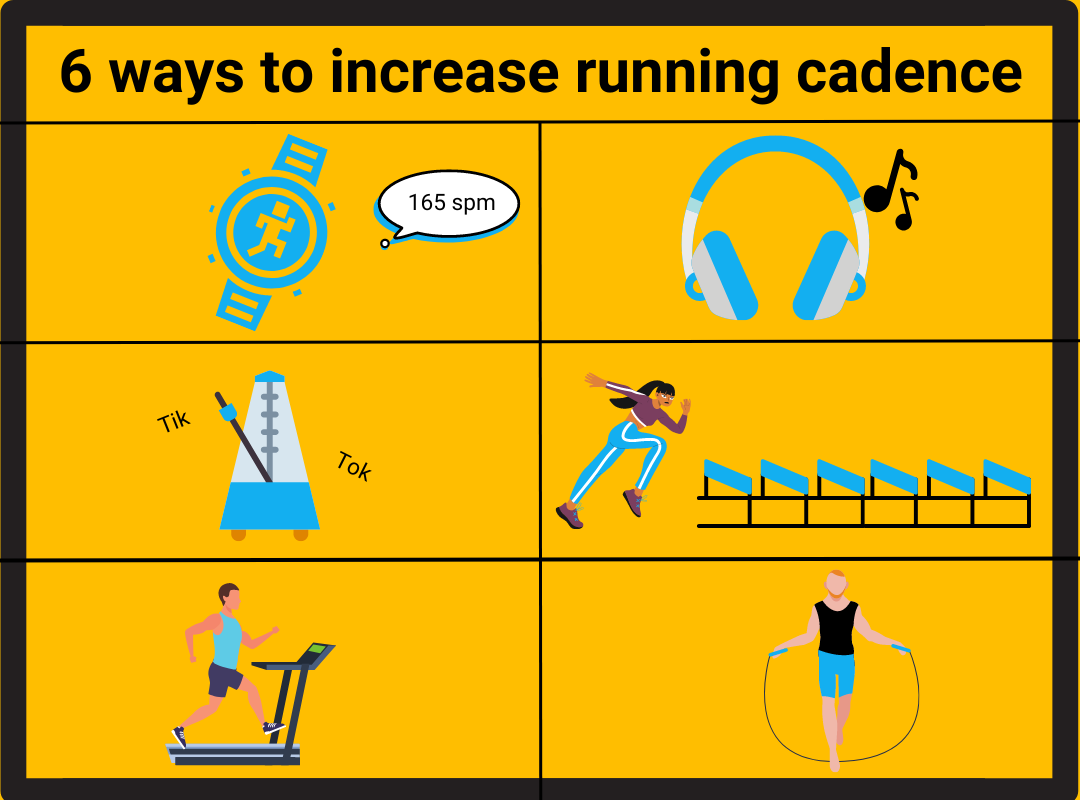

As with many adaptations, the key is to do it step by step. Try to first increase cadence with a couple of steps per minute. Your sports watch is a good tool to monitor your step rate during these cadence workouts.

A treadmill can also help to improve your cadence. Since you have no fluctuations in speed, you can really focus on increasing cadence without increasing pace.

Some coaches also recommend cadence exercises like jumping rope, speed ladder drills and (mini) hurdle drills. So far I haven’t found any literature that confirms the effectiveness of these cadence workouts.

Music to increase your steps per minute

Listening to music while running is a very common practice. If you do this, you probably noticed the rhythm and beat of the music can affect your step rate.

Literature shows that music can help to increase stride frequency. The runners received a playlist with music songs that had a rhythm that was 10% higher than their normal cadence. After 6 weeks, their preferred cadence was increased by 7,3%.

The researchers used a software tool to increase the beats per minute of the songs to their desired bpm. A more practical way for you to get started is by using existing playlists like Running on 160 bpm songs or Running Songs 170 bpm on Spotify.

Researchers advise against using songs that have a bpm that is more than 10% higher than your current step rate.

Metronome to increase your step rate

If you don’t like to run with music, you can also set an alarm on your sports watch whenever the cadence is too low. You can expect a similar increase in cadence over time with this training method.

Using a metronome is another way of getting sound cues to increase step rate. The benefit is that you can set your beats per minute very precisely.

I’m guessing many of you will find it anyoing to run with a metronome sound. I actually liked it more than the music playlist, because it leaves “headspace” for thoughts. You can also easily listen to it for a minute, unplug and repeat after a while. Let me know your experience!

Can my running cadence also be too high?

Both beginners and trained runners tend to have a step rate (slightly) below the ideal step rate. Therefore, chances are not so great that your cadence is too high.

However, if you deliberately try to increase your cadence above your normal cadence, you could end up with a cadence that is too high.

If you did a lot of high cadence drills in the past, you might wonder if your cadence is too high now. You could start with comparing your cadence with others, using this calculator.

So far I haven’t read any scientific paper that showed runners have a cadence that is too high. So personally, I would not worry about it too much.

Injured? Increase your cadence!

Cadence interventions are common to prevent- and rehabilitate from injury. This is the idea behind it:

If you increase your cadence, you take more steps for a given distance. This intuitively means that the load on your body is distributed over more steps. As a result, the load per step should be lower.

It’s a bit similar to riding your bike. When you increase your RPM (cycling cadence), by gearing down while maintaining the same speed, you need less force per pedal stroke.

But is this true in running too? And if so, does increasing your running cadence prevent injuries?

Increasing your cadence decreases impact on hip, knee and ankle

According to this scientific study, increasing your current cadence by 7.3% results in a decrease of 5.6% in peak force.

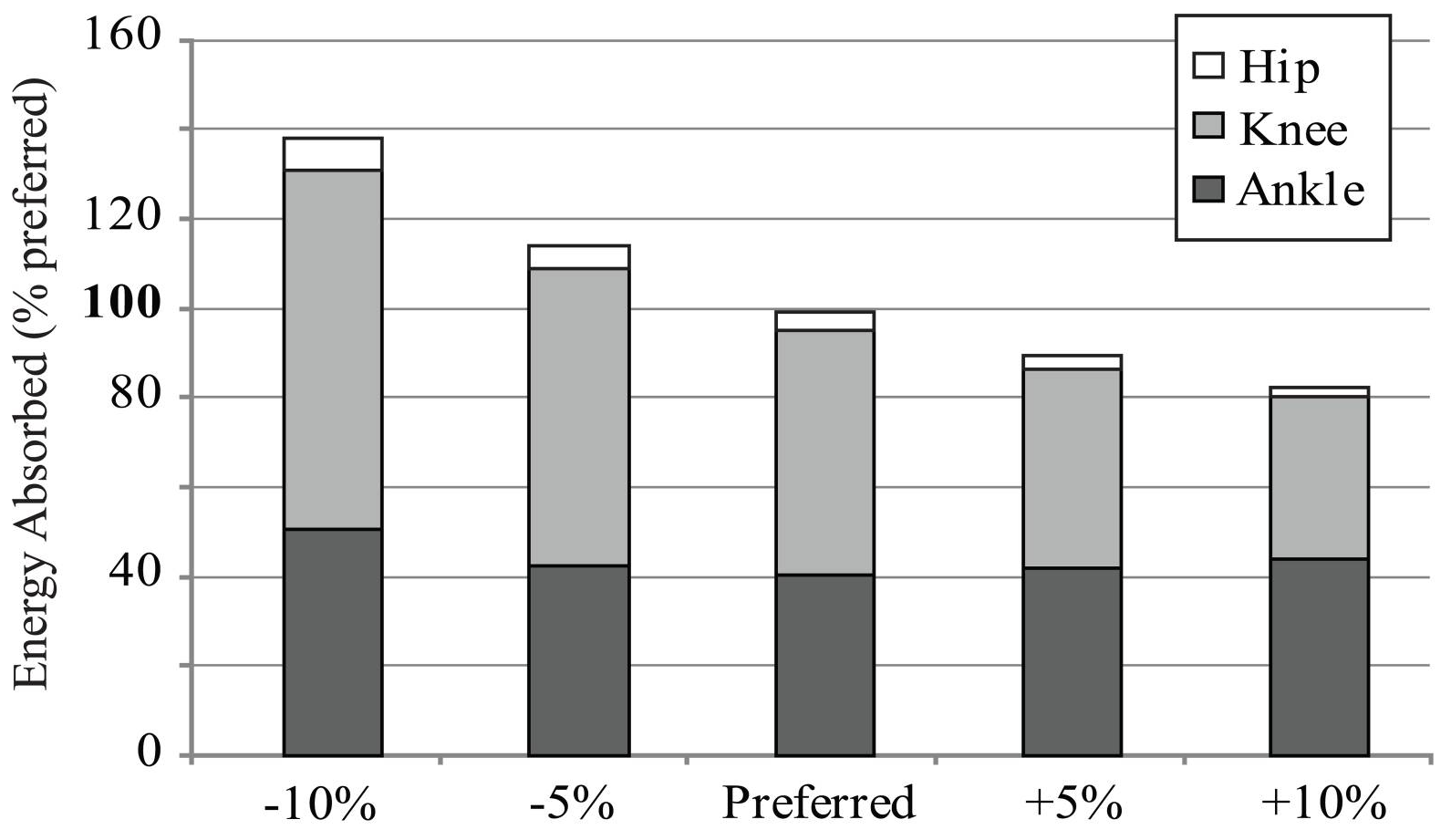

To be a bit more specific, another study shows that significantly less energy is absorbed at the knee and hips when you increase your preferred cadence by 10%. In other words, there is less impact on your knees and hips when increasing step rate.

These findings, together with a decrease in ankle energy absorption, are confirmed by this systematic literature review.

Whether this is a result of increased cadence or decreased step length (two sides of the same coin) is unclear, but probably also irrelevant for you as a runner.

Do high impact forces cause injuries?

Just because the impact decreases when increasing your step rate, does not necessarily mean this also helps prevent injuries.

However, this scientific paper states that “high impact forces are associated with development of common running related injuries, such as medial tibial stress syndrome, Achilles tendinopathy, plantar fasciitis and patellofemoral pain syndrome.”

Increasing your cadence decreases Patellofemoral pain

When looking at a specific injury like patellofemoral pain*, increasing cadence seems to be effective. This study shows that a cadence increase of 10%, decreases patellofemoral pain within 4 weeks.

A cadence increase of 10%, decreases patellofemoral pain within 4 weeks.

The runners started with a stride rate of 165.93 ± 7.38 steps per minute before they increased their stride rate by 10% (while maintaining the same running speed). Unfortunately running speed was not mentioned, making it hard to compare with your own cadence.

*Note that patellofemoral pain is not the same as patellar tendinitis, which is also known as jumper’s knee.

Effect of cadence on shin injuries

Another specific running injury is a shin injury.

This study found that “runners with a step rate less than or equal to 164 steps per minute were 6.7 times more likely to sustain a shin injury compared to runners who ran greater than or equal to 174 steps per minute.”

Runners with a step rate ≤ 164 steps per minute are 6.7 times more likely to sustain a shin injury.

Summarizing relationship between cadence and injuries

As you’ve read, several studies show that increasing your current step frequency has a positive effect on injury prevention and rehabilitation. Often an increase of 10% is suggested.

However, as you understand, the effect of the intervention depends on your current cadence. If you already have a good cadence, increasing it by 10% will not help a lot. Moreover, you can’t keep increasing your cadence by 10%.

Since cadence can be highly individual, several studies (1, 2) don’t see any difference between the cadence of runners who injure themselves and those who don’t.

My advice? Compare your current cadence with others via this calculator and play around with increasing it a bit, if it feels good.

Factors that influence the ideal stride frequency

You’ve had the opportunity to compare your running cadence with a large group of uninjured long-distance runners. However, this group consists of young runners of a certain age, body height, experience etc. This group may not represent you.

So let’s look at some factors that influence the ideal cadence. Running speed and body height are probably the most obvious. Let’s look at each factor separately, using the latest scientific insights.

Speed: easy run vs race

Does running cadence change with speed? Yes it does!

When you increase running speed, you automatically increase stride frequency AND stride length.

To be more specific, this scientific paper suggests that on a group level (N = 256), runners increase their cadence with 6 steps per minute, every time they increase their speed with 1 m/s. The cadence formula that describes their runners best:

Cadence = 150,02 + 6,012 * speed (m/s)

As a result, you’ll take less steps per minute during an easy run compared to a race or sprint. Which is no surprise, is it?

“Runners increase their cadence with 6 steps per minute, every time they increase their speed by 1 m/s.”

However, this also implies that you should always mention a speed or pace when talking about a cadence. Knowing this, it makes no sense to say something like “a cadence of 180 spm is ideal”, without mentioning the corresponding pace.

This could also explain why many professionals have a higher stride frequency than you and me. It’s because they run much faster.

Height: tall runners vs short runners

Another factor that intuitively impacts your stride frequency is body height. Just think about a short runner and a tall runner, running at the same speed. Do you imagine them having the same stride frequency? Probably not.

Length – and in particular leg length – impacts running cadence. As you would expect: runners with a shorter leg length have a higher step rate, at the same running speed.

According to this scientific paper, running experience and leg length account for 36% of the variability in step rate.

When combining running speed and leg length, approximately 50% of the variance in cadence is explained, according to this paper.

If we put it in numbers, for each 5 cm increase in leg length, stride frequency is reduced by 2 strides per minute, according to Van Oeveren et al. This equals 4 steps per minute.

“For each 5 cm increase in leg length, stride frequency is reduced by 4 steps per minute.”

Similar to speed, this implies that you should always take body height into account when talking about a cadence. Tall runners with long legs will automatically run with a lower cadence (on a group level), compared to short runners.

Distance: sprint vs marathon

When the running distance increases, the running speed often decreases. Also: the higher the running speed, the higher the step rate. When we combine these two, it will come as no surprise that the cadence of a 100m sprinter is higher than the cadence of a marathon runner.

But what if we normalise for speed?

Does running distance impact the (ideal) running cadence? Do you need a different cadence when running a 5k compared to a marathon or ultra?

I guess energy efficiency and load become more important in longer running events. So far I haven’t found any specific answer to whether you should change your cadence, depending on the distance you run.

However, it is interesting to know that even the very best ultra-runners have a wide average step frequency range: between 155 and 203 spm (!). This data was collected during the 100-km World Championship road race.

Terrain: trail vs road vs track vs treadmill

Does off-road running or trail running require a different cadence than road or even indoor (treadmill) running?

Literature shows that we automatically increase our cadence when running on a treadmill, compared to overground running. So far, I haven’t found any studies comparing trail running with road running.

However, I can imagine trail runners need to be able to run at a wider range of running cadences than road or track runners. Simply because the off road terrain changes all the time. This results in a variety of different speeds and step rates.

Therefore it makes sense that trail runners also train with a wider variety of step rates than road or track runners.

Uphill vs downhill running

Whenever I run uphill or downhill, I start to focus on step length and therefore step rate. Sounds familiar? But should you increase or decrease it?

When running at the same speed, self-selected cadence does not differ between normal level running (no incline or decline) and -6 degree downhill running.

Deliberately increasing or decreasing cadence while running downhill did not have a positive effect. In fact, staying close to the self-selected cadence minimises energy cost and impulse loading.

Deliberately increasing or decreasing cadence while running downhill or uphill does not have a positive effect.

The same is true when running uphill at a 3 degree incline. Although runners tend to automatically increase their stride frequency when running uphill. This increase was not significant. Deliberately increasing or decreasing cadence did not have a positive effect.

So you don’t need to worry about cadence when running uphill or downhill. Isn’t that comforting? It is to me!

Level: beginners vs elite

What is a good running cadence for beginners? And do elite runners have a higher running cadence? Let’s see what literature has to say about these questions.

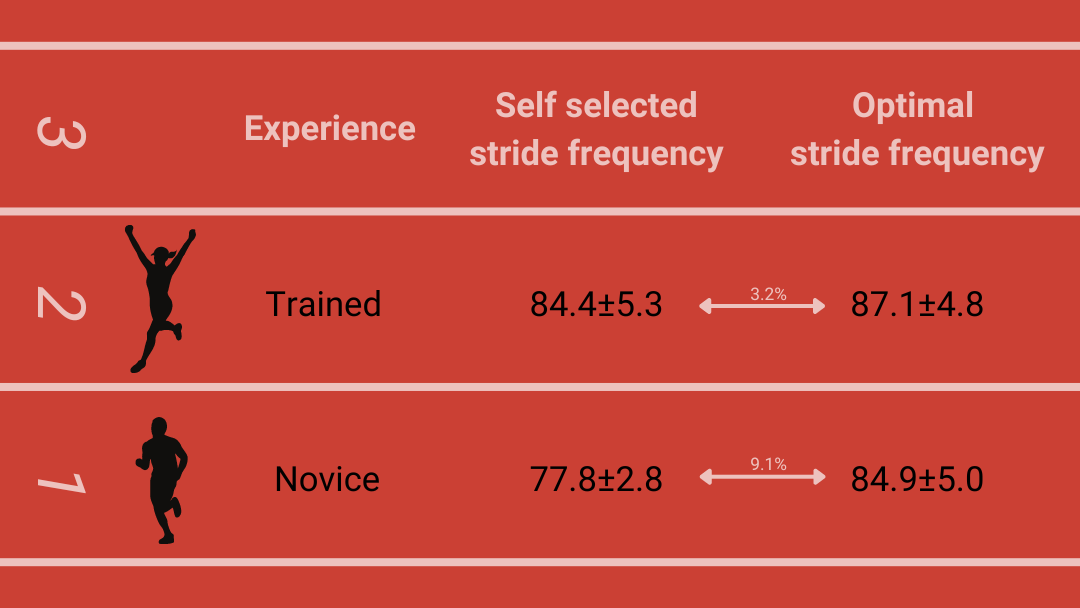

Over the years, runners tend to increase their stride frequency, according to this longitudinal study. When comparing trained runners with untrained runners, we see a similar effect. Trained runners have a step rate that is roughly 4% higher than beginners, at the same running speed.

This study found that novice runners not only have a lower cadence than experienced runners, but their cadence is also further away from the ideal running cadence. The ideal running cadence was determined based on energy expenditure.

On average, beginners had to increase their cadence with 14 steps per minute to match their ideal running cadence. Which is quite a lot, don’t you think?

Beginners have to increase their cadence with 14 steps per minute to match their ideal running cadence.

The practical implication is that most beginners should increase their running cadence.

When combining leg length, running speed and running experience, 55% of the variance in cadence is explained.

Fatigue: beginning of the race vs end of the race

When you think of running when fatigued, you probably picture yourself crawling forward in a less effective way. But does cadence change when we get tired?

Some researchers say stride frequency decreases in a 1 hour near maximal effort at a constant speed. On average cadence decreased about 2 steps per minute.

This could be due to neural fatigue.

However, others found that runners actually increased their step rate by 5% on average, in a 24-h ultra run. This could be an adaptation to a “safer” running style to reduce impact load.

In other words, it could go in both directions. Or in neither one of them.

Age: young vs old

We already saw that elite runners tend to have a higher cadence than beginners. But what happens when we get older? Does running cadence decrease with age?

The short answer is: no it doesn’t. In fact, it’s quite the opposite.

When comparing runners with varying ages from 19 to 65 years old, older runners actually have a higher cadence.

To give an example, this study found that on average, a 40-year-old takes 1,4 steps per minute more than a 30-year-old, at a speed of 3 m/s. At a speed of 5 m/s the difference becomes even bigger: 2,2 steps per minute.

A 40-year-old takes 2,2 steps per minute more than a 30-year-old, at a speed of 5 m/s.

Here’s the cadence of professionals

As stated earlier, Jack Daniels noticed that almost all his elite distance runners had a cadence above 180 spm.

This is probably due to the fact that all elite runners have one thing in common. They run very fast.

Let’s look at some elite runners, just to have some running cadence examples.

Eliud Kipchoge – setting world record marathon

Let’s look at the running cadence of Eliud Kipchoge.

By now, you know that the step frequency depends on speed and body height. So before we share Kipchoge’s stride frequency, first some facts:

Kipchoge run the Berlin marathon (42.195 km) in 2:01:09. His speed equals a little over 21 km/h or 2:52 (mm:ss) per kilometer or 5,8 m/s.

According to Wikipedia, Kipchoge’s height equals 167 cm.

On average his cadence turned out to be roughly 190 steps per minute during the marathon. As a result, the full marathon took him about 23000 steps. His stride length must have been around 185 cm.

According to the cadence calculator – which is based on scientific literature – Kipchoge runs with a cadence that is 10% above what you would expect for a runner with his body height and running speed.

Usain Bolt – winning gold Olympic Games 100m

Let’s compare that with Usain Bolt’s running cadence, for the sake of fun.

Bolt is obviously a totally different runner. His body height equals 195 cm. His sprint distance is only 100m.

His height has a negative effect on the ideal step frequency. However, his speed requires a high step frequency.

At the 2012 Olympics, Bolt ran 100 meters in 9,64 seconds. He took 41 steps to get to the finish.

As a result, his cadence was above 255 steps per minute.

Femke Bol – becoming European Champion 400m

Height: 184 cm

Running speed: 8,1 m/s

Distance: 400m

Time: 49,44 seconds (European Championships 2022)

Steps to cover 400 meters: 179 steps

Running cadence: 217 steps per minute

Brigid Kosgei – winning London Marathon

Height: 170 cm

Running speed: 5,1 m/s

Distance: 42.195 km (marathon)

Time: 2:18:58 (London Marathon 2020)

Running cadence: 195 steps per minute

Measuring cadence with sport technology

Measuring your cadence is easy. All you need is a stopwatch.

A simple smartphone app like Runkeeper can also help you track your cadence. Unfortunately, as far as I know, Strava does not track running cadence yet.

Of course you can also use a sports watch. Similar to Polar, some Garmin watches track cadence, others require a Garmin accessory called Running Dynamics Pod.

Apple watches also track running cadence. Both your live running cadence and your average cadence.

If you want to dive deeper into your running metrics, it makes sense to measure beyond the sports watch possibilities. Here are 2 examples of hardware tools that measure running cadence and more:

Wrap up

I hope this article answered all your cadence questions. Now it’s time to get out there and do something with it!

Did I leave your question unanswered? Let me know, so I can update the article!

Feel free to share this article with your coach and running friends.

Subscribe to my newsletter to get a notification whenever I add new insights to this article, or share similar articles on different topics. You can subscribe via the form at the bottom of this page.

Founder of Molab, Human Movement Scientist and Freelance Content Marketer.